Job Creators

, Somewhere over the Pacific OceanOn Thursday, the House passed the JOBS Act by an overwhelming margin, and the Senate expects to pass a similar bill soon. The act is part of a growing swell of activity promoting entrepreneurship. An amusing startup meta-market has taken flight, creating huge sales for books like Eric Ries‘s The Lean Startup. You might get the sense from all the pro-entrepreneurship hype, that starting a business is easy; everyone should do it! And really, what’s not to love about the idea of creating lots of new businesses? Still, every good idea has doubters. Scott Kirsner wondered in the Boston Globe, “Is it possible that Boston is spawning too many start-ups?”, and Sean Parker said at Le Web that “Rather than having a bunch of small ideas, diluted by a bunch of teams, we have to concentrate the great talent out there to change the world.”

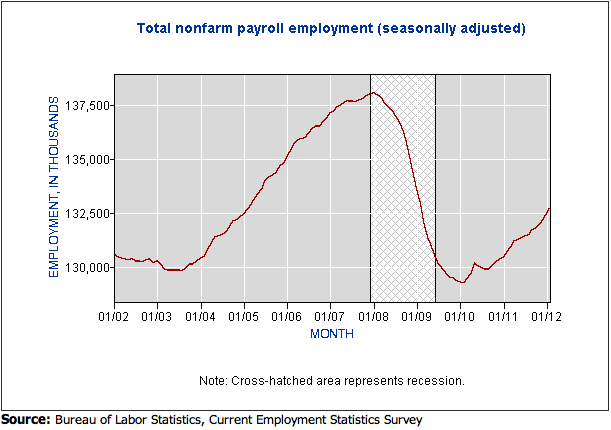

Job creation has been a hot topic since the mortgage-backed securities bubble burst, destroying existing jobs by the millions. President Obama unveiled his first plan to create or save 2.5 million jobs even before he was inaugurated, and held a high powered jobs summit a year later, in December 2009.

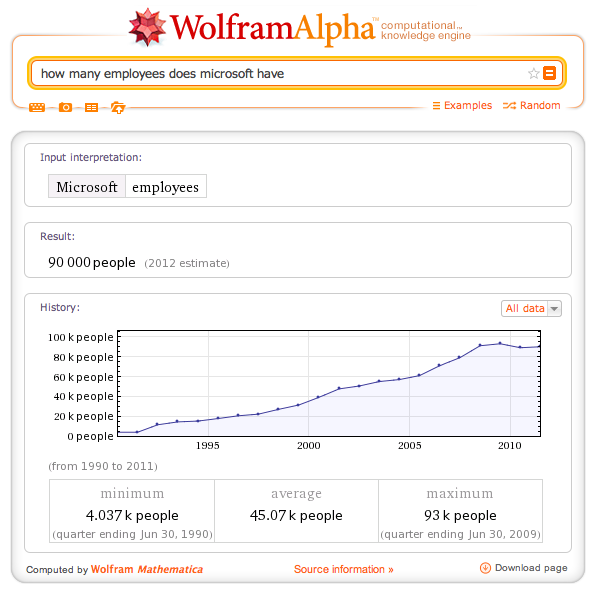

In August 2010, a TechCrunch article by Vivek Wadhwa caught my attention. I took it at face value at the time. This week the JOBS Act reminded me of Wadhwa’s article in a roundabout way. First I saw Steve Case‘s tweet announcing that the JOBS Act had passed the House, and read Case’s February article supporting the act. Case wrote, “Startups have created 40 million American jobs in the past three decades — all the net-new jobs produced during that time period.” Really? I asked Case what defines a startup and where I could find more information. His head of communications referred me to the Kauffman Foundation. Wadhwa had made a similar claim in his earlier article, writing, “Startups aren’t just an important contributor to job growth: they’re the only thing. … So we can’t count on the Intels or Microsofts to create employment.” What?!? Intel and Microsoft will never create net jobs? They’re doomed to shrink forever? Wadhwa’s article also cited a report from the Kauffman Foundation, so I went to take a look at the underlying data from the Census’s Business Dynamics Statistics.

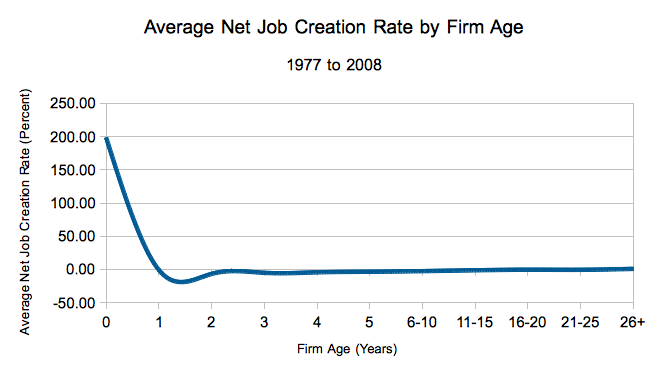

The reports that startup proponents are fond of citing segment the data by “firm age” and define a startup as a firm that’s existed for less than three years. Intel and other big growth companies are the outliers among the longer tenured firms. On average, firms older than three years are job destroyers, and firms younger than three years are job creators. Those are facts derived directly from the BDS data. Three years is a completely arbitrary boundary. The data actually indicates that firms older than one year are net job destroyers. Beyond the facts, there are a lot of fallacies that might seem like logical conclusions on the surface.

Fallacy One: Big Old Company X doesn’t create jobs. That’s like concluding that ostriches fly because you know that most birds do. Intel and Microsoft both have long histories of net job creation; they didn’t stop creating jobs when they hit age three.

Fallacy Two: Startups are more successful than older firms. Job creation is not success; it’s a means to attempt customer creation that fails more often than not.

So why do young companies create more net jobs than older firms? Because the definition is biased. There’s just enough subtlety in the bias that it sounds interesting to say, “Startups create all the net jobs,” but the bias isn’t far off from segmenting the data by job creation and saying, “Growing companies create all the net jobs.” On the day a firm hires its first employee, it’s a net job creator. Most firms don’t lay off their first employee the next day. Somewhere between a day and three years, there’s an interesting number: the mean time to job destruction. Two year old firms have created net jobs in only one year between 1977 and 2009: 2000. One year old firms were net job creators in about half the years between 1977 and 2009. On average, even firms between one and two years old have destroyed net jobs since 1977. Firms less than one year old created net jobs in every year.

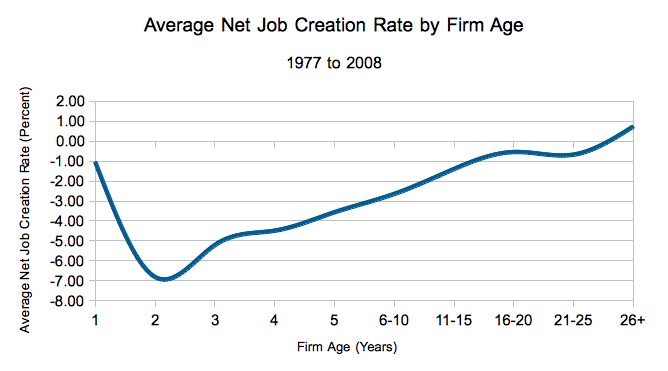

There’s only one other segment of firms by age that appears to create net jobs. The oldest firms tracked by the BDS appear to benefit from survivorship bias in the same way startups benefit from youth bias. Although firms between two and 25 years old are all net job destroyers, an upward trend in net job creation as firm age increases is unmistakable. Firms older than 26 years may turn out to be net job creators; there’s not enough data to say so conclusively yet. In the seven years in which the BDS data includes firms older than 26 years, 2003-2009, those firms have created net jobs four times. The old firms destroyed significant net jobs in only one year — 5.5% in 2009 — which I presume is an indicator of fallout from the bursting of the mortgage bubble.

On the policy front, legislation like the JOBS Act promotes starting up more businesses. Books like Eric Ries’s The Lean Startup and Len Schlesinger‘s Just Start, and seed stage accelerators like Paul Graham‘s Y Combinator and David Cohen‘s TechStars teach entrepreneurship with the intent of creating more success stories from all those startups. Most of them will still fail. Schlesinger, president of Babson College, notes that over some short period of time, startups’ net job creation is still zero. Nevertheless, he advocates entrepreneurship as a life skill. After all, if you can start a business that provides your income in the short term, and you know how to start another business if one fails, you control your own full employment destiny. And you can benefit from an entrepreneurial approach even if you never start a business of your own.